Menu

- Main Page

- About us

- Research

- Publications

- Links

- Contact

- Archiwum

- Holocaust. Studies and Materials

the Center's Journal - NIGHT WITHOUT AND END - »FAILED CORRECTION«

- Wybór źródeł

- EHRI PL

News

Programme of Center's academic seminars for winter term 2025

We are pleased to announce the return of our scientific seminar series in less than a month, and warmly invite all interested parties to attend. The seminars will be held on the second or third Wednesday of each month, both in person at the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polis...

M. Turski Historical Award of Polityka for Justyna Majewska

It is with undisguised pride we report that our colleague Dr. Justyna Majewska has been awarded the Marian Turski POLITYKA Historical Prize for her book debut, "Mury i szczeliny. Przestrzenie getta warszawskiego /Walls and Slits. Spaces of the Warsaw Ghetto". We are very happy and...

Call for Articles - Holocaust Studies and Materials 2026

Call for Articles 2026 Call for Articles Connecting scholarly reflection on the Holocaust to the present - new sources and technologies in research The past decade has seen a breakthrough in Holocaust research, both in terms of the availability of archival sources and the digital ...

Farewell to Marian Turski

It is with profound sorrow that we bid farewell to Marian Turski—a distinguished journalist, historian, and Survivor. An extraordinary man whose voice resonated deeply, he not only shared the lessons of the past but actively championed courage, solidarity, and empathy in the face of evil. ...

Center in EHRI PL consortium

Polish Center for Holocaust Research of the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, together with the E. Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute and the Center for Jewish Studies of the University of Lodz, are creating a national node of the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure within the framework of ERIC

NEWSLETTER

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 18, R. 2022

Warszawa 2022

PAMIĘTNIK

PAMIĘTNIK

Kalman Rotgeber

oprac. Aleksandra Bańkowska, wstęp Jacek Leociak

Warszawa 2021

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 17, R. 2021

Warszawa 2021

NIE WIEMY CO PRZYNIESIE NAM KOLEJNA GODZINA ...

NIE WIEMY CO PRZYNIESIE NAM KOLEJNA GODZINA ...

Dziennik pisany w ukryciu w latach 1943-1944

Moszek Baum, oprac. Barbara Engelking, tłum. z jidysz Monika Polit

Warszawa 2020

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 16, R. 2020

Warszawa 2020

.jpg) Aryjskiego Żyda wspomnienia, łzy i myśli

Aryjskiego Żyda wspomnienia, łzy i myśli

Zapiski z okupacyjnej Warszawy

Sewek Okonowski, oprac. Marta Janczewska

PISZĄCY TE SŁOWA JEST PRACOWNIKIEM

PISZĄCY TE SŁOWA JEST PRACOWNIKIEM

GETTOWEJ INSTYTUCJI ...

'z Dziennika' i inne pisma z łódzkiego getta

Józef Zelkowicz, tłum. z jidysz, oprac. i wstęp. Monika Polit

Warszawa 2019

CZYTAJĄC GAZETĘ NIEMIECKĄ ...

Dziennik pisany w ukryciu w Warszawie w latach 1943-1944

Jakub Hochberg, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking

Warszawa 2019

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 15, R. 2019

Warszawa 2019

.jpg) Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 14, R. 2018

Warszawa 2018

DALEJ JEST NOC. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski

DALEJ JEST NOC. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski

red. i wstęp Barbara Engelking, Jan Grabowski

Warszawa 2018

ŻADNA BLAGA, ŻADNE KŁAMSTWO ...

ŻADNA BLAGA, ŻADNE KŁAMSTWO ...

Wspomnienia z warszawskiego getta

Stanisław Adler, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Marta Janczewska

Warszawa 2018

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 13, R. 2017

Warszawa 2017

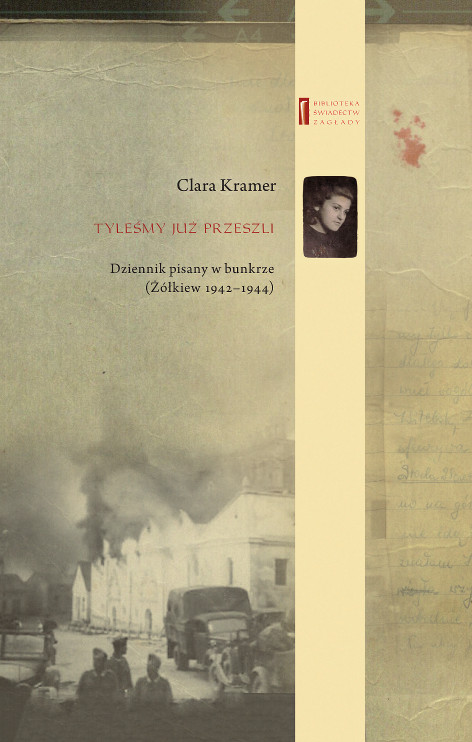

TYLEŚMY JUŻ PRZESZLI ...

TYLEŚMY JUŻ PRZESZLI ...

Dziennik pisany w bunkrze (Żółkiew 1942-1944)

Clara Kramer, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Anna Wylegała

Warszawa 2017

WŚRÓD ZATRUTYCH NOŻY ...

WŚRÓD ZATRUTYCH NOŻY ...

Zapiski z getta i okupowanej Warszawy

Tadeusz Obremski, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Agnieszka Haska

Warszawa 2017

PO WOJNIE, Z POMOCĄ BOŻĄ, JUŻ NIEBAWEM ...

PO WOJNIE, Z POMOCĄ BOŻĄ, JUŻ NIEBAWEM ...

Pisma Kopla i Mirki Piżyców o życiu w getcie i okupowanej Warszawie

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking i Havi Dreifuss

Warszawa 2017

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 12, R. 2016

Warszawa 2016

.jpg) SNY CHOCIAŻ MAMY WSPANIAŁE ...

SNY CHOCIAŻ MAMY WSPANIAŁE ...

Okupacyjne dzienniki Żydów z okolic Mińska Mazowieckiego

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking

Warszawa 2016

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 11, R. 2015

Warszawa 2015

Mietek Pachter

Mietek Pachter

UMIERAĆ TEŻ TRZEBA UMIEĆ ...

oprac. B. Engelking

Warszawa 2015

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 10, t. I-II, R. 2014

Warszawa 2015

OCALONY Z ZAGŁADY

OCALONY Z ZAGŁADY

Wspomnienia chłopca z Sokołowa Podlaskiego

tłum. Elżbieta Olender-Dmowska

red .B. Engelking i J. Grabowski

Warszawa 2014

ZAGŁADA ŻYDÓW. STUDIA I MATERIAŁY

ZAGŁADA ŻYDÓW. STUDIA I MATERIAŁY

vol. 9 R. 2013

Pismo Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów IFiS PAN

Warszawa 2013

... TĘSKNOTA NACHODZI NAS JAK CIĘŻKA CHOROBA ...

... TĘSKNOTA NACHODZI NAS JAK CIĘŻKA CHOROBA ...

Korespondencja wojenna rodziny Finkelsztejnów, 1939-1941

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Ewa Koźmińska-Frejlak

Warszawa 2012

Raul Hilberg

PAMIĘĆ I POLITYKA. Droga historyka Zagłady

tłum. Jerzy Giebułtowski

Warszawa 2012

Monika Polit

Monika Polit

"Moja żydowska dusza nie obawia się dnia sądu."

Mordechaj Chaim Rumkowski. Prawda i zmyślenie

Warszawa 2012

.jpg) Dariusz Libionka i Laurence Weinbaum

Dariusz Libionka i Laurence Weinbaum

Bohaterowie, hochsztaplerzy, opisywacze. Wokół Żydowskiego Związku Wojskowego

Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2011, nr. 7; Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Jan Grabowski

Jan Grabowski

JUDENJAGD. Polowanie na Żydów 1942.1945.

Studium dziejów pewnego powiatu

Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Stanisław Gombiński (Jan Mawult)

Stanisław Gombiński (Jan Mawult)

Wspomnienia policjanta z warszawskiego getta

oprac. i wstęp Marta Janczewska

Warszawa 2010

Holocaust Studies and Materials

Journal of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research

Warssaw 2010

.jpg) Żydów łamiących prawo należy karać śmiercią!

Żydów łamiących prawo należy karać śmiercią!

"Przestępczość" Żydów w Warszawie, 1939-1942

B. Engelking, J. Grabowski

Warszawa 2010

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2010, nr. 6; Warszawa 2010

Wybór źródeł do nauczania o zagładzie Żydów

Ćwiczenia ze źródłami

red. A. Skibińska, R. Szuchta

Warszawa 2010

.jpg) W Imię Boże!

W Imię Boże!

Cecylia Gruft

oprac. i wstęp Łukasz Biedka

Warszawa 2009

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2009, nr. 5; Warszawa 2009

.jpg) Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie

Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie

Barbara Engelking i Dariusz Libionka

Warszawa 2009

Reportaże z warszawskiego getta

Reportaże z warszawskiego getta

Perec Opoczyński

Warszawa 2009

Notatnik

Notatnik

Szmul Rozensztajn

Warszawa 2008

.jpg) Holocaust

Holocaust

Studies and Materials.

English edition

2008, vol. 1; Warsaw 2008

.jpg) Źródła do badań nad zagładą Żydów na okupowanych ziemiach polskich

Źródła do badań nad zagładą Żydów na okupowanych ziemiach polskich

Przewodnik archiwalno-bibliograficzny

Alina Skibińska, wsp. Marta Janczewska, Dariusz Libionka, Witold Mędykowski, Jacek Andrzej Młynarczyk, Jakub Petelewicz, Monika Polit

Warszawa 2007

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2007, nr. 3; Warszawa 2007

Prowincja noc.

Życie i zagłada Żydów w dystrykcie warszawskim

Warszawa 2007

.jpg) Utajone miasto.

Utajone miasto.

Żydzi po 'aryjskiej' stronie Warszawy [1941-1944]

Gunnar S Paulsson

Kraków 2007

Sprawcy, Ofiary, Świadkowie.

Sprawcy, Ofiary, Świadkowie.

Zagłada Żydów, 1933-1944

Raul Hilberg

Warszawa 2007

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2006, nr. 2; Warszawa 2006

"Jestem Żydem, chcę wejść!".

Hotel Polski w Warszawie, 1943.

Agnieszka Haska

Warszawa 2006

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2005, nr. 1; Warszawa 2005

.jpg) 'Ja tego Żyda znam!'

'Ja tego Żyda znam!'

Szantażowanie Żydów w Warszawie, 1939-1943.

Jan Grabowski

Warszawa 2004

'Szanowny panie Gistapo!'

'Szanowny panie Gistapo!'

Donosy do władz niemieckich w Warszawie i okolichach, 1940-1941

Barbara Engelking, Warszawa 2003

aaa

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 18, R. 2022

Warszawa 2022

PAMIĘTNIK

PAMIĘTNIK

Kalman Rotgeber

oprac. Aleksandra Bańkowska, wstęp Jacek Leociak

Warszawa 2021

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 17, R. 2021

Warszawa 2021

NIE WIEMY CO PRZYNIESIE NAM KOLEJNA GODZINA ...

NIE WIEMY CO PRZYNIESIE NAM KOLEJNA GODZINA ...

Dziennik pisany w ukryciu w latach 1943-1944

Moszek Baum, oprac. Barbara Engelking, tłum. z jidysz Monika Polit

Warszawa 2020

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 16, R. 2020

Warszawa 2020

.jpg) Aryjskiego Żyda wspomnienia, łzy i myśli

Aryjskiego Żyda wspomnienia, łzy i myśli

Zapiski z okupacyjnej Warszawy

Sewek Okonowski, oprac. Marta Janczewska

PISZĄCY TE SŁOWA JEST PRACOWNIKIEM

PISZĄCY TE SŁOWA JEST PRACOWNIKIEM

GETTOWEJ INSTYTUCJI ...

'z Dziennika' i inne pisma z łódzkiego getta

Józef Zelkowicz, tłum. z jidysz, oprac. i wstęp. Monika Polit

Warszawa 2019

CZYTAJĄC GAZETĘ NIEMIECKĄ ...

Dziennik pisany w ukryciu w Warszawie w latach 1943-1944

Jakub Hochberg, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking

Warszawa 2019

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 15, R. 2019

Warszawa 2019

.jpg) Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 14, R. 2018

Warszawa 2018

DALEJ JEST NOC. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski

DALEJ JEST NOC. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski

red. i wstęp Barbara Engelking, Jan Grabowski

Warszawa 2018

ŻADNA BLAGA, ŻADNE KŁAMSTWO ...

ŻADNA BLAGA, ŻADNE KŁAMSTWO ...

Wspomnienia z warszawskiego getta

Stanisław Adler, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Marta Janczewska

Warszawa 2018

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 13, R. 2017

Warszawa 2017

TYLEŚMY JUŻ PRZESZLI ...

TYLEŚMY JUŻ PRZESZLI ...

Dziennik pisany w bunkrze (Żółkiew 1942-1944)

Clara Kramer, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Anna Wylegała

Warszawa 2017

WŚRÓD ZATRUTYCH NOŻY ...

WŚRÓD ZATRUTYCH NOŻY ...

Zapiski z getta i okupowanej Warszawy

Tadeusz Obremski, oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Agnieszka Haska

Warszawa 2017

PO WOJNIE, Z POMOCĄ BOŻĄ, JUŻ NIEBAWEM ...

PO WOJNIE, Z POMOCĄ BOŻĄ, JUŻ NIEBAWEM ...

Pisma Kopla i Mirki Piżyców o życiu w getcie i okupowanej Warszawie

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking i Havi Dreifuss

Warszawa 2017

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 12, R. 2016

Warszawa 2016

.jpg) SNY CHOCIAŻ MAMY WSPANIAŁE ...

SNY CHOCIAŻ MAMY WSPANIAŁE ...

Okupacyjne dzienniki Żydów z okolic Mińska Mazowieckiego

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Barbara Engelking

Warszawa 2016

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 11, R. 2015

Warszawa 2015

Mietek Pachter

Mietek Pachter

UMIERAĆ TEŻ TRZEBA UMIEĆ ...

oprac. B. Engelking

Warszawa 2015

Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

nr 10, t. I-II, R. 2014

Warszawa 2015

OCALONY Z ZAGŁADY

OCALONY Z ZAGŁADY

Wspomnienia chłopca z Sokołowa Podlaskiego

tłum. Elżbieta Olender-Dmowska

red .B. Engelking i J. Grabowski

Warszawa 2014

ZAGŁADA ŻYDÓW. STUDIA I MATERIAŁY

ZAGŁADA ŻYDÓW. STUDIA I MATERIAŁY

vol. 9 R. 2013

Pismo Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów IFiS PAN

Warszawa 2013

... TĘSKNOTA NACHODZI NAS JAK CIĘŻKA CHOROBA ...

... TĘSKNOTA NACHODZI NAS JAK CIĘŻKA CHOROBA ...

Korespondencja wojenna rodziny Finkelsztejnów, 1939-1941

oprac. i wstępem opatrzyła Ewa Koźmińska-Frejlak

Warszawa 2012

Raul Hilberg

PAMIĘĆ I POLITYKA. Droga historyka Zagłady

tłum. Jerzy Giebułtowski

Warszawa 2012

Monika Polit

Monika Polit

"Moja żydowska dusza nie obawia się dnia sądu."

Mordechaj Chaim Rumkowski. Prawda i zmyślenie

Warszawa 2012

.jpg) Dariusz Libionka i Laurence Weinbaum

Dariusz Libionka i Laurence Weinbaum

Bohaterowie, hochsztaplerzy, opisywacze. Wokół Żydowskiego Związku Wojskowego

Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Zagłada Żydów.

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2011, nr. 7; Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Jan Grabowski

Jan Grabowski

JUDENJAGD. Polowanie na Żydów 1942.1945.

Studium dziejów pewnego powiatu

Warszawa 2011

.jpg) Stanisław Gombiński (Jan Mawult)

Stanisław Gombiński (Jan Mawult)

Wspomnienia policjanta z warszawskiego getta

oprac. i wstęp Marta Janczewska

Warszawa 2010

Holocaust Studies and Materials

Journal of the Polish Center for Holocaust Research

Warssaw 2010

.jpg) Żydów łamiących prawo należy karać śmiercią!

Żydów łamiących prawo należy karać śmiercią!

"Przestępczość" Żydów w Warszawie, 1939-1942

B. Engelking, J. Grabowski

Warszawa 2010

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2010, nr. 6; Warszawa 2010

Wybór źródeł do nauczania o zagładzie Żydów

Ćwiczenia ze źródłami

red. A. Skibińska, R. Szuchta

Warszawa 2010

.jpg) W Imię Boże!

W Imię Boże!

Cecylia Gruft

oprac. i wstęp Łukasz Biedka

Warszawa 2009

Zagłada Żydów.

Studia i Materiały

R. 2009, nr. 5; Warszawa 2009

.jpg) Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie

Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie

Barbara Engelking i Dariusz Libionka

Warszawa 2009

Reportaże z warszawskiego getta

Reportaże z warszawskiego getta

Perec Opoczyński

Warszawa 2009

Notatnik

Notatnik

Szmul Rozensztajn

Warszawa 2008

.jpg) Holocaust

Holocaust

Studies and Materials.

English edition

2008, vol. 1; Warsaw 2008

.jpg) Źródła do badań nad zagładą Żydów na okupowanych ziemiach polskich

Źródła do badań nad zagładą Żydów na okupowanych ziemiach polskich

Przewodnik archiwalno-bibliograficzny

Alina Skibińska, wsp. Marta Janczewska, Dariusz Libionka, Witold Mędykowski, Jacek Andrzej Młynarczyk, Jakub Petelewicz, Monika Polit

Warszawa 2007

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2007, nr. 3; Warszawa 2007

Prowincja noc.

Życie i zagłada Żydów w dystrykcie warszawskim

Warszawa 2007

.jpg) Utajone miasto.

Utajone miasto.

Żydzi po 'aryjskiej' stronie Warszawy [1941-1944]

Gunnar S Paulsson

Kraków 2007

Sprawcy, Ofiary, Świadkowie.

Sprawcy, Ofiary, Świadkowie.

Zagłada Żydów, 1933-1944

Raul Hilberg

Warszawa 2007

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2006, nr. 2; Warszawa 2006

"Jestem Żydem, chcę wejść!".

Hotel Polski w Warszawie, 1943.

Agnieszka Haska

Warszawa 2006

Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały

R. 2005, nr. 1; Warszawa 2005

.jpg) 'Ja tego Żyda znam!'

'Ja tego Żyda znam!'

Szantażowanie Żydów w Warszawie, 1939-1943.

Jan Grabowski

Warszawa 2004

'Szanowny panie Gistapo!'

'Szanowny panie Gistapo!'

Donosy do władz niemieckich w Warszawie i okolichach, 1940-1941

Barbara Engelking, Warszawa 2003

aaa

Nowy Swiat St. 72, 00-330 Warsaw; POLAND;

Palac Staszica room 120

e-mail: centrum@holocaustresearch.pl

NIGHT WITHOUT END - Failed correctiion - Karolina Panz

Karolina Panz see in PDF![]()

Institute of Slavic Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences

orcid.org/0000-0003-2019-7624

centrum@holocaustresearch.pl

Response to the Review

by Tomasz Domański Entitled Correcting the Picture? Reflections on the Sources Used in "Night Without an End. Fate of Jews in Selected Counties of Occupied Poland"”1]

(Polish-Jewish Studies, Institute of National Remembrance [Warsaw, 2019])

As the author of the chapter “Nowy Targ County” published in Night Without End, I have long pondered whether to reply to Tomasz Domański’s review, because I have considerable doubts if the author of the review published by the Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN) read my text. It is the first time I have come across a situation where the reviewer employs opinions of another reviewer while voicing his reservations about a text and never reaches beyond them.

Domański, citing the manuscript of a then unpublished review by Dawid Golik (an employee of the Cracow Branch Office of the IPN; the review was published in February in Zeszyty Historyczne WiN 47, the periodical in which I plan to reply to Golik’s review), attacked me for applying “the method of putting forward hard claims a priori, literally without presenting any archival findings” (31), and for “drawing conclusions based on two testimonies” (30). Truly, I have no idea what my study could be a result of if not archival research — it has 647 footnotes, where I cite materials from Polish, German, Israeli, and American archives. The following remark written by Domański concerns my conclusion: “The sources that were available to me demonstrate that in the autumn of 1942 on the territory of Kreis Neumarkt the key role in the methodical hunt for victims in the mountains and forests was that of organized 12-men peasant guards and informal gangs that pretended to be peasant guards, made up of young men, who knew each other quite well” (Panz, vol. 2, 290). I never thought that I would be forced to explain to a reviewer that the phrase “sources available to me” is not identical with the materials that I used as sources of quotations in summarizing the several pages long description of the fate of Podhale Jews hiding in Nowy Targ county in the early days following Operation Reinhardt. Domański writes, referring to me: “She seems to forget that the forests were also combed by members of uniformed German formations: the blue police and the Forstschutzkommando (Forest Guard)” (31). I will ignore the lack of personal civility presented here, and stress what I had pointed out in the citation quoted by Domański: sources available to me show the key role of the peasant guard and gangs in the hunt for Jews in Nowy Targ county in the autumn of 1942. As for the Forstschutzkommando, I did not ‘forget’ about it; nowhere did I find any mention of its members taking part in the events that I describe. Very little is known about the forest guard in Nowy Targ county, and over several years of archival research I found no collection of documents regarding the activity of this formation. It would be desirable if the reviewer, who formulates such a critical remark about my work, could identify materials which support such an opinion. But Domański does no such thing. It is also untrue that I ‘forgot’ about the blue policemen and their role in hunting for Jews in hiding. I discussed, among others, the activity of several constables from Jordanów, who murdered Jews in the local cemetery (Panz, vol. 2, 270 and 348), constables from Czorsztyn, who transported Anna Furcowa, a convert, to her execution (ibid., 338), and constables from Ciche, who tracked down the Relek family in the village for several weeks (ibid., 292). However, I have found no sources that would confirm the involvement of blue policemen in combing the forests. The materials that I gathered mention only that peasants brought Jews to blue police stations or showed policemen to places where Jews were hiding.

In the same paragraph, Domański attacks me for a lack of information on “how the awareness of the existence of informers (whom she mentions), who checked whether the locals are complying with German regulations, influenced the behavior of peasants, who feared repressions” (31). The fact that he mentions informers, referring to my statement about Jews hiding in the forests and barns in Podhale, is further evidence that even if he did read my study, he certainly never analyzed it. I discuss informers in Kreis Neumarkt in a section entitled “Aryjska strona w Kreis Neumarkt” [The ‘Aryan’ side in Kreis Neumarkt] and exclusively in the context of Jews who did not originate from Podhale and were staying in the county (mostly in its larger localities) under an assumed identity. I reconstructed the scale and character of the informers’ operation and their ties to the Gestapo and Kripo on the basis of, for instance, reports of the chief of counterintelligence of the Cracow Home Army (Armia Krajowa, AK) and the files of the informers’ post-war trials (Panz, vol. 2, 317–323). German repressions in the context of the attitudes of peasants from Nowy Targ county towards their Jewish neighbors who sought rescue are comprehensively discussed elsewhere in my study, in the section entitled “Sprawiedliwi z Kreis Neumarkt” [Righteous from Kreis Neumarkt] (ibid., 343–355), where I mention seventeen Poles who paid with their lives for helping Jews. I write about the repressions, fear, dilemmas, and dramatic choices of those who helped and those who refused help. Hence, I do not know why the author of “Correcting the Picture?” concluded that I did address this topic.

Domański’s next observation about my text concerns the nature of the following sentence, which concludes the description of murders committed in the county during Operation Reinhardt: “In each and every one of these places, Poles watched the Jews who were familiar to them dying, heard their screams, touched corpses and breathed the air filled with the overpowering smell of their dead bodies. No one could have remained indifferent to this. For no one had the victims been distant or anonymous. And during the next phase of the Holocaust, the attitude of those Polish witnesses became critical for the Jews who tried to save themselves.” (ibid., 275). According to the author, the language I employ in this sentence is not appropriate for a scholarly publication. In the twenty pages preceding this sentence, I describe the omnipresent terror and death, based to a large extent on the testimonies of the Polish inhabitants of the county who witnessed the extermination of their neighbors from behind the wall, outside the window, or on the other side of the fence. In the sentence criticized by Domański every word is based on their testimonies, most of which contained very graphic details, which I omitted because I did not intend to shock the readers with the brutality of those events. Expressing the reality of the Holocaust poses a great challenge to scholars, including myself, even though I have been describing it for as many as fourteen years. I do not know what language Domański would use to describe it, since he has not published any major work on this topic. Before he chooses the language of his description, I encourage him to familiarize himself with the scholarly debate on ways of expressing the Holocaust, which has been going on for years (for instance, Probing the Limits of Representation. Nazism and the ‘Final Solution’, ed. Saul Friedländer [Cambridge–London: Harvard University Press, 1992]; Bartłomiej Krupa, Opowiedzieć Zagładę. Polska proza i historiografia wobec Holocaustu (1987–2003) [Cracow: Universitas, 2013]; Zagłada. Współczesne problemy rozumienia i przedstawiania, ed. Przemysław Czapliński, Ewa Domańska [Poznań: Wydawnictwo „Poznańskie Studia Polonistyczne”, 2009]; Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz [University of Chicago Press, 2008]; Bartosz Kwieciński, Obrazy i klisze. Między biegunami wizualnej pamięci Zagłady [Cracow: Universitas, 2012]; Sonia Rusznikowska, Każdemu własna śmierć. O przywracaniu podmiotowości ofiarom Zagłady [Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich, 2014]).

The author of “Correcting the Picture?” makes a direct reference to my chapter once more, stating: “In Nowy Targ county the term ‘elites’ does not appear in reference to representatives of the Jewish community” (25). It does not appear because, as I mention at the very beginning of my study, pre-war Nowy Targ county had no major factories and no fortunes were made there (Panz, vol. 2, 220). Most Podhale Jews were petty merchants and craftsmen. The representatives of the local intellectual elites, including a small number of physicians and lawyers, escaped east from the nearing Germans and remained under Soviet occupation. Many of them survived in exile in the interior of the USSR, for instance, in Siberia. A narration about ‘new elites’ (a term which in Domański’s opinion requires a detailed analysis, 25) in the context of the Jewish communities of Nowy Targ county would require a category of description that does not match that reality at all, as the Judenrats were made up of the same petty traders and craftsmen who had been members of the pre-war kahals. Consequently, I do not write about ‘elites’ but about the activity of Jewish councils (Panz, vol. 2, 225–228). Nor do I write about Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst, because no Jewish Police formations were created anywhere in the county I am writing about (ibid., 231). This time too Domański fails to indicate any sources which could disprove my narration.

The microhistorical perspective we adopted is based on an in-depth analysis of the sources to learn about the specificity of every county. The lack of ‘new elites’ among the Jews of Podhale during the occupation was one of the many characteristic features of Nowy Tag county, which I learned about through a careful examination of the materials I collected.

I am describing the reality that is revealed to me by the sources. This makes the following comment Domański addressed to all authors of Night Without End sound all the more curious: “The post-war depiction of Polish-Jewish relations was narrowed down […] to negative examples, mostly of murders of the Jews” (7). I spent several years researching the post-war fate of Jews in Podhale, where 34 Jews, including women and children, died during 1945–1947. Those victims were former prisoners of German concentration camps or labor camps in the USSR and individuals who had miraculously survived mass executions. In Nowy Targ county during the post-war period the Jews faced abuse, were beaten, shot at, threatened, and killed. Cows grazed on the graves of the Jewish inhabitants murdered during the war. This is the image of post-war Polish-Jewish relations preserved in the sources. Even though I would like to broaden it to include positive aspects of that reality, I have found nothing that would enable me to do so. One would expect that after accusing us of intentionally restricting this depiction, the reviewer would present some sources disproving the dramatic image of post-war Polish-Jewish relations on the territory which I researched. Since Domański fails to do so, his statement remains nothing more than a manifestation of his wishful thinking and the preconceptions with which he approached our study.

Within the space of one review, Domański combines his claim about our “presupposed thesis about Polish complicity” (24) with a sentence about our “programmatic focus exclusively on the fate of the Jewish victims” (4). As for the latter, I fully agree that Poles and their attitudes towards the extermination of their Jewish neighbors were not the object of our research. From the very beginning, my research was guided by our plan to find out about the fate of Jews in Nowy Targ county, with how the Poles were entangled with that fate or influenced its shape at certain moments. But our intention to examine those moments cannot be equated with a thesis about the Poles’ “complicity”. It should be stressed that we do not use this expression anywhere in our book, which means that its use is Domański’s invention. The author of “Correcting the Picture?” does not seem to notice that our “programmatic focus” on the fate of Jews results from the fact that for decades the extermination of Jewish inhabitants of small towns has been programmatically excluded from historical studies of those places and it has remained an unrecalled reality: devoid of the victims’ names, faces, and individual fates. Domański himself, in his book on German repressions in the Kielce countryside (Represje niemieckie na wsi kieleckiej 1939–1945 [Kielce 2011]). failed to mention the murders of local Jews.

At the beginning of his review, Domański writes that “[a]ny attempt to fill the gaps in our knowledge on the period of the German occupation is praiseworthy” (3). However, “Correcting the Picture?” and the actions undertaken by the IPN on the occasion of its publication prove what great problems emerge when after dozens of years of silence, the gaps are filled with content which is difficult to accept by those who declare their attachment to historical truth, but in fact defend the myth of an innocent Poland.

[1] Tomasz Domański, Korekta obrazu? Refleksje źródłoznawcze wokół książki Dalej jest noc. Losy Żydów w wybranych powiatach okupowanej Polski, https://ipn.gov.pl/pl/aktualnosci/65746,Korekta-obrazu-Refleksje-zrodloznawcze-wokol-ksiazki-Dalej-jest-noc-Losy-Zydow-w.html, access 14 March 2019. As the English translation of this brochure has not been published yet, the page numbers refer to its Polish edition, with the quotations translated by the translator of this review. (translator’s footnote)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)